This entry is immensely long, and it's also about one of the top two most interesting things I've experienced in Argentina.

In Full View

Twice a week Tribunal Oral en lo Criminal Nº1, a courthouse

in La Plata, Buenos Aires closes off the street in front of it, and holds a

trial on the rights abuses during the late 70s. This period in Argentina, from

1976-1983, is often called the “Dirty War”, except for by its victims, who

claim it was not a war, because a war needs two armies. Instead they use the

term “el Proceso” (“the Process”) to refer to 7 years of a government preying

on any citizen who spoke against it. While it is important to remember that the

citizens’ opposition was not pacifistic, they did not deserve what happened.

The

trial my class and I went to see was for information, not for a verdict. The defendant

on the stand Miguel Osvaldo Etchecolatz, the Director of Investigations for the

Police of Buenos Aires during the Proceso, had already been condemned to life

in jail in 2006. The trial was purely to find information, about a particular occurrence

during those years.

Anyone

with identification can enter a courtroom and watch a trial, and my school

group was joined by art students and some middle aged observers. One woman with

long white hair was a founding member of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a

group that still demands justice for the children the government secretly

kidnapped during the Proceso. The only rules the courthouse gave us were you

must be over fourteen, because the themes were so heavy, and you could not

bring in food or water, lest you throw them at someone. This implied the due

bitterness surrounding the trials. The courthouse staff gave us official

wristbands and let us enter.

Set the Stage

The

courtroom itself appeared to be an old theater. The seats the public sat in

looked just like those for a play-going audience, and a red curtain was pulled

to the side above the stage where sat the judge, defendant, and lawyers. Despite

its theatrical origins, it was a very plain building, devoid of any decorations.

A somber place dedicated to a practical job: finding the truth.

The

judge sat facing the audience, along with two assistants. (It surprised me to

see that one had dyed her hair magenta). On the right, rows of prosecuting

lawyers with laptops and coffee cups, faced inwards, towards center stage. On

the left, a cage jutted out into the audience, and here, protected by five

guards in bulletproof jackets reading “SPF”, sat the defense. One guard had a

riot shield, and they spent the time watching the audience and the case.

Throughout the trial more guards with radios and black berets walked the floor.

Etchecolatz

rose, a normal looking older man with white hair and a gray suit, and sat at a

desk, his back to the audience, facing the judge. This is what evil looks like, I told myself, knowing I was seeing a

man who had presided over murder and torture, and yet I felt no repulsion. This

was just a man.

Clara Anahí as photographed by her grandmother days before the attack. I borrowed it from: http://www.apdhlaplata.org.ar/espacio/n31/esp12.htm

Memory of Family

Etchecolatz had been called in from

prison to give his account on the case of Casa 30. This house had been home to

five Montoneros, anti-government rebels, and two of theirs baby girl. Most

importantly, the house hosted a secret printing press the Montoneros used to

distribute their political flyers. To cover it up, they raised and sold rabbits

(as food, not pets). Because of this, the novel written about Casa 30 is called

“Casa de Los Conejos”, or “House of Rabbits”.

Etchecolatz and the police attacked

the house in 1976, killing everyone inside it, save, perhaps, for the three

month old baby, Clara Anahí Mariani. Neighbors reported seeing the police take

the baby from the house, and it was not an uncommon practice for police to

kidnap children and raise them as their own. Estimates say 400 of these

“disappeared” children are going about their lives today, completely unaware of

their real identities. Clara Anahí’s grandmother is still looking for her; if

she has survived this long, she turned 35 last August. But even if Clara Anahí

was taken alive from the house, she could have been hit by a car at age 15 and

died, or died of cancer at age 30; if alive she might not even still be in the

country. It soon became clear that Etchecolatz’s objective in the trial was to

say the daughter was dead, and thus that the search should stop, and that he was

not complicit in anything blameworthy.

Designing Justice

Trials in Latin America follow a different structure from the U.S.’s

precedent-based system. The codified system in Latin America places more trust

in written evidence and reviewing data, while the USA emphasizes oral evidence

from witnesses. Watching this case, another difference became obvious: in

Argentina, the judge, in addition to the lawyers, has a chance to examine the

defense, and the defense can be brought in to be questioned again, if new

evidence appears. For an hour or more, our judge questioned Etchecolatz

Summary: Ray of Truth, Fog of Lies

The events of the day at Casa 30

began to become clear as the trial proceeded. The facts that Etchecolatz and

other accounts agreed upon were that Etchecolatz had arrived at Casa 30 along with

other military officers, that several officers entered the house, and that the

five Montoneros were killed. During the attack on Casa 30, Etchecolatz was on

the roof of the adjacent house, along with a man with a bazooka.

Etchecolatz handwaved over his

involvement, trying to suggest that his entire participation in the conflict

had been to merely exist on the roof, instead of having any job assigned to

him, or having been involved with organizing the event. The police director

also attempted to put a nationalistic, positive spin on the actions of the

police in the Proceso, presenting them as a civilian, humanitarian group, and

putting all blame for torture on the military. Part of Etchecolatz’s aim was

also to insist that the Proceso had not been unilateral aggression: “[Los

Montoneros] también tenía resistencia” (“The Montoneros also had resistance”) he said, and claimed

the guerrillas had killed 270 policemen.

There were a few notable flaws with

Etchecolatz’s account. First, he, the director of police, had followed someone

else’s orders to go to the house, and yet had not been assigned any role to do

while there. He hadn’t been on the roof to catch people fleeing, he insisted,

nor even really to observe. Secondly, all the Montoneros were to be killed and their

bodies burned, Etchecolatz reported, yet he claims neither saw bodies nor

flames nor heard shots. In regards to the detention centers, in Etchecolatz’s

world, the police were merely there to take care of the abducted people’s

health and nutrition, the rest was the military’s job. Finally, despite physical

evidence and numerous first hand accounts, Etchecolatz denied that torture was

a common occurrence.

In Defense of a Nation

When Perón ran for president in 1945, it was immediately

after World War II and photos of the concentration camps were just leaking out

to full public view. The U.S. ambassador, Braden, accused Perón of supporting

Hitler and harboring Nazis. To explain to the class why this was such a harsh,

campaign-damaging accusation, my history teacher clarified: it would be like

saying you supported the ESMA, a major detention center used in the Proceso.

Argentina is a place where those responsible for the Proceso draw a quicker gut

reaction, a more immediate repulsion, than Nazis. In my human rights classes

and history classes, no one could even question that the military committed

horrors.

Just thirty years after the

Proceso, and in a society where everyone knows the full extent of the abuses

committed, I heard Etchecolatz continue to assert that his actions were fully

justified. While I had been warned that most of the Proceso’s human rights

criminals were unrepentant, it still felt unreal. Etchecolatz referred to those

kidnapped by the government as “terroristas” (terrorists), and “prisioneros de la guerra” (prisoners

of war”).

“Tenían que perseguirlo [y] matarlos como ratas” (“We had to chase them [and]

kill them like rats”), he insisted; The Proceso was a campaign to protect country’s

institutions, and allow Argentina to live in peace.

Words for War

Among Etchecolatz’s description of the military government,

stark nationalistic phrases continued to pop up. He told how the military government had tried to “recuperar

la verdad” (“to recover the truth”), “recuperar lo que ha perdido” (“to recover

what had been lost”), “[asegurar] respecta para sus instituciones” (“to ensure

respect for its institutions”), “[asegurar que Argentina puede] vivir en paz” (“to

makes sure that Argentina could live in peace”), “sofocar una situación de

ofensa” (“to suffocate an offensive situation”), and “afrentar el enemigo” (“to

confront the enemy”).

Brainwashed Language

During the Proceso itself, the government enacted a huge

propaganda campaign in which they repeatedly used nationalistic images to present

their work as glorious and righteous and encourage belief in their side. If the

police and guerrillas clashed, the newspaper was bound to report that the

police had eliminated a subversive, or, if luck went the other way, that a

policeman had been murdered by terrorists.

Euphemisms made torture seem less

offensive: a “sumbarino” (submarine) is a tasty treat similar to hot chocolate,

made by dropping a bar of chocolate in warm milk. When the government attached

the name “submarino” to a form of torture, it became easier for soldiers to

distance themselves from what they were actually doing: waterboarding a victim

in water tainted with feces and urine. In a 1984-esque

attempt to cut down on subversive thought, the word “revolution” was banned,

even including in reference to science.

Play by Play

It feels the most honest representation is to report the

event as straightforwardly as possible, including giving the original Spanish,

as that is the most accurate and true wording. I will translate as closely as I

can.

What Did You Do?

It

began with the judge questioning:

“¿Cuándo

se producen muertes era porque hay sido resistencias?”

When killing occurred

was it because there had been resistance?

I didn’t

catch all of Etchecolatz‘s response. It was something like:

“Somos ciudadanos .. . . no es así

permitir abusos, no recibí ningún orden de torturas. . .”

We are citizens . .

.it is not so that abuses were allowed, I didn’t receive any order to torture.

. .

In a somewhat jumbled way,

Etchecolatz went on to detail the event. The government forces attacked Casa 30

because it had a printer for “panfletos terroristas” (“terrorist pamphlets”) in

the house. He believed that everyone in Casa 30 was killed, as the order had

been to leave no one alive (“nadie quedar con vida”). Officers entered that

house, the Montoneros inside resisted (at least he emphasized that he thought this was what happened), and,

presumably, said Etchecolatz, the officers killed them all. Still, he reminded

his listeners “no vi nada” (“I didn’t see anything”), and “no oí disparos” (“I didn’t hear shots”). Etchecolatz

said that “fueran carbonizados a todos en la casa” (“Everyone

in the house was burned to ashes”), but when the judge asked he admitted that

he had not seen fire or felt heat. Witnesses in other meetings on this case had

also not seen fire. According to my human rights teacher, it was a common

practice for the military/police to take away the bodies of their victims, so

as to leave no tangible evidence. If Etchecolatz could suggest the bodies were

burned, he would not have to explain what actually happened to them. But he

could not blatantly contradict the testimonies of other witnesses.

The

judge picked at the story:

“¿Por

qué estabas allá si hiciste nada? ¿Cómo fue estar en el techo sin ver nada?

¿Por qué estabas en el techo? Los disparos de afuera . . .estabas allá parar

matar a alguien que saliera de la casa?”

Why were you there if

you didn’t do anything? How was it that you were on the roof and saw nothing?

Why were you on the roof? The shots outside . . .where you there to kill anyone

who left the house?

Etchecolatz:

“Estaba allá por

parte de posición en la policía”

I was there as part of

my position in the police.

He

continued, saying that he was only support and that no one gave him an order.

Judge:

“¿Dices

que no hecho ningún tipo de exceso? ¿Nunca influido por exceso del gobierno de

este época?”

You said that you

never committed any type of excess? You were never influenced by the excesses

of the government of this time?

Etchecolatz:

“Lo que

cumplí estaba acuerdo del ley”

What I did was in

agreement with the law.

Judge:

“Si recibió un orden a matar, debió

negar”

If one received an

order to kill, one should refuse it.

Etchecolatz:

“¡Ningún

orden matar!”

There wasn’t any order

to kill!

Etchecolatz continued, saying that he had only received

orders to go to the roof.

Vanished Children

Judge:

“¿Hijos

de personas desaparecidos eran recobrados?”

Were the children of

the disappeared recovered?

Etchecolatz:

“No sé.”

I don’t know.

In

regards to the child Clara Anahí, Etchecolatz merely mentioned that the

people in the house

“enseñaba a niña revistas subversivos” (“taught the girl subversive magazines”);

this is no doubt a major reason the military would have taken her. El Argentino, a newspaper present at the

trial that day, quoted Etchecolatz as saying “No puedo asegurar que la

criatura estaba adentro, pero si estaba adentro, la criatura no pudo salir con

vida” (“I can’t be sure that the child was inside, but if she was inside, the

child could not have left with her life”). Despite this claim, it is known,

thanks to a testimony in El Argentino,

that the police had at one point attempted to sell Clara Anahí to her

grandmother, something that strongly suggests the child was not killed at the

house. Relatively recently, it was thought that the daughter of the owner of Clarín, an important newspaper, was in

fact Clara Anahí. The daughters looked similar, were of the right age, and it

was known that the newspaper owner’s daughter was adopted under strange

circumstances. For much time the newspaper owner’s lawyers stalled and resisted

requests for a DNA test, then suddenly agreed to it, presumably because they

discovered through other evidence that the daughter was not a match.

A Skeptical Audience

In response another line of questioning, Etchecolatz told

the judge that whatever happened to pregnant women was the decision of the

clandestine detention centers that held them, and was not his fault. The

police, he said, were only responsible for the health and food of the

prisoners, nothing else. The police’s orders, he reiterated, were to “mantener higiene, cuidar salud

física, no interrogar” (“to maintain hygiene, to take care of physical health,

not to interrogate”). The military was the one who had the

responsibility for the prisoners and the detention centers.

However, Etchecolatz said he did

remember one instance of a pregnant prisoner. When this girl gave birth, he

said, the staff at the detention center bought her presents and a card. Groans

of disbelief rose from the audience when they heard this. He couldn’t remember

the girl’s name or last name. But she was from La Plata, the neighborhood the

trial was in, he said, and the police, because it was a humanitarian issue,

took charge of letting her family know.

By this point, the audience had seen

thousands such trials, and knew to expect these sort of responses from the

accused. In 1986 it was prohibited to try anyone for human rights abuses

committed during the Proceso and since then many criminals were pardoned. About

a decade ago, then-president Néstor Kirchner re-opened the trials. The lying

and lack of repentance was nothing new to the audience of this trial, and the

bitterness was clear. When Etchecolatz announced that “caminaba en lo más sucio de la sociedad y

no me contaminaba” (I walked in the filthiest part of society, and it

didn’t contaminate me”) members of the audience laughed aloud in scorn.

Remember with Care

When the judge returned to asking Etchecolatz about the

events on the day at Casa 30, Etchecolatz tried to say he didn’t remember much

of anything. Occasionally,

in the trial Etchecolatz would get flustered responding to

questions, would answer in a stream of “Sísísísísí” or “Nononono.” After

prodding, he admitted he did remember how he arrived (in a car), but not who

drove it, and admitted that he did now remember that others were in the car

with him. He did not remember, however, who ordered the attack on the “casa de

los terroristas” (“the terrorists’ house”). As Etchecolatz was the director of the police, it is a fair

bet that he himself ordered the attack.

Here the lawyers took over.

One asked:

“¿Si no

estaba parte de investigaciones, si solo cuidaba salud física, porque estaba a

la Casa 30?”

If you weren’t there

as part of the investigations, if you only took care of physical health, why

were you at Casa 30?

I don’t believe Etchecolatz answered this one.

The white building or this flat roof here is likely where Etchecolatz was during the attack.

House of Holes

After the trial, we went to see Casa 30, a small gray cement building. A

whole window and most of the wall was blasted out, presumably by the bazooka,

and deep holes marked around the door and wall. Glancing through a bullet hole

on one wall we could see inside the house, a wall similarly pockmarked by bullets.

The roof Etchecolatz must have stood on could not have been more than 8 feet

from the door of Casa 30.

The house itself has been preserved as it was since the attack

Epilogue: The Curtain Doesn’t Fall

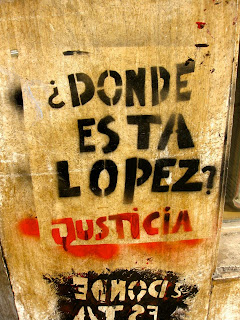

The

face and name Jorge Julio López is something I've seen graffitied all across

Buenos Aires, on walls, on tiles in La Plaza de Mayo, and especially in La

Plata. Eventually, I learned why.

in La Plata

at Plaza de Mayo

This man had been kidnapped and personally tortured by

Etchecolatz from 1976-1979. During the first trial of Etchecolatz, López was a

major witness, and his testimony against Etchecolatz was invaluable: In

addition to recounting to his own horrific experience, López had seen

Etchecolatz execute five people.

Though the Proceso trials offer a form of resolution

and validation, testifying is nonetheless extremely painful for the victims. In

a documentary on this trial, called “Un Claro Día de Justicia” (“A Clear Day of

Justice”), I saw López struggling to get the words out. He remembered a woman

named Patricia who was imprisoned with him; he was the only one of them with a

chance of leaving the detention center alive, she told him, and she begged

López to find her parents or her brothers and tell them to “dame un beso a mis

hijas” (“give a kiss to my daughters for me”). Recounting, reliving, this

moment, López’s voice almost failed him, it was with painful effort that he

managed to speak. The older man’s hands trembled, like a hummingbird flapping,

so much that he couldn’t pick up a glass of water; someone had to hold it out

for him to sip.

López during the trial. (Photo credit to Haydeé Dessal y Elena Luz González Bazán at http://www.villacrespomibarrio.com.ar/2011/septiembre/ciudad/derechos%20humanos/lopez%20en%20fotos.htm)

During

the days of this trial, López, a white haired, 77 year old man with children,

vanished. In the midst of recounting his horrifying disappearance,

disappearances ceased to be a memory and became the state of his life once

again. (The trials continued without López, and Etchecolatz was sentenced to

life in prison.) This was five years ago. López still has not been found.

It

was 23 years after the end of the Proceso, supposedly in a better government

and better world, and yet, with López’s abduction, the disappearances were

re-opened. Since then, there have been accusations the police’s fruitlessness

in the case is deliberate. The satire magazine, Revista Barcelona, publishes a weekly piece ridiculing the police’s

attempts to find López. Clara Anahí and Jorge Julio López have still not been

found, but until they, or their final resting places are, the trials will still

go on, and the protests will continue in the Plaza de Mayo.

Calendar titled "How many days without López?"; Displayed in ESMA, previous site of a navy clandestine detention center.

Links: