Finals ended this week, thankfully, and last night was my program's goodbye ceremony. (Located at a surprisingly ritzy place, where two types of celebration fused: the dance party disco balls and music mixed with with an elegant dinner party scene with waiters politely carrying appetizers).

Now I'm off to volunteer for 18 days on a farm in the province of Mendoza, known for it's wine and, unfortunately, I'm learning, for being even hotter than Buenos Aires in November. It is sweltering here, with a high humidty, yet Starbucks has started putting little ice skaters on its advertisements. I'm volunteering as part of a WOOF program, where I'll work 6-7 hours a day and get free meals and shelter (I'm camping with a friend from the program). The town I"m going to apparently has very good apples, and I think that's about all I know. Wish me luck!

Friday, November 25, 2011

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Tourists like lists (or so I hope)

I think it's time to give a shot at writing something more touristy, so here goes: a set of list and tips for anyone vacationing in the city.

The Fairs, ranked

1. Ferria de Los Inmigrantes – this is not a regular fair, but if you’re around in September, it makes a great lunch spot. You won’t get the South American feel, because countries like India, Germany, Russia, and more are represented in the booths, but this fair is one of the few not aimed at tourists. Whereas San Telmo is teeming with souveneirs, the main things to buy here are food, and hats, clothes, and trinkets from other countries. What makes this fair stand out is the dancing. A stage is set up in front of a perfect picnic spot, with dancing and singing throughout the day. Smaller dances seem to break out randomly among costumed members of other booths.

2. Ferria de los Matadores: There’s dancing at this fair, too, though it’s less diverse. The dance is a folklore style, accompanied by music, and I heard rumor that sometimes the fair has horse tricks, though I was disappointed to find they weren’t happening the day I went. It seems to be luck of the draw what you’ll get to see. While this fair is also touristy, full of leather belts, wooden flutes, chocolate, cheap bread, and alcohol, the prices are excellent (a bottle of wine for 13 pesos, for instance).

3. San Telmo fair: This fair happens every Sunday and is notable for its sheer size. The fair consumes several city blocks in many directions, and you can walk for hours still seeing new things. It is a very touristy fair, and there’s a pressure to shop for souvenirs the whole time. Here and there in the fair will be musicians playing guitar or even on a metal bowl, and mimes for children. Some cool highlights were boxes made out of a single orange peel, the ubiquitous soft wool sweaters with llama designs, and some delicious homemade pastries from a woman pushing a cart.

4. Tigre’s Fruit Fair: this fair on the river offers good fruit smoothies, and a large collection of items ranging from earrings to furniture in the nearby shops. None of it’s items are truly unique, but you can get cheap yerba in bulk, and lots of fruit.

5. Ferria Recoleta at Plaza Francia: This is another weekly fair, and a nice place to peruse on the way to the cemetery or one of the nearby art museums. All the products are touristy, meaning a quick way to pick up souvenirs, but a bit pricier just for that reason. You’ll find things like mate gourds, leather belts, and shirts.

6. Gay Pride Parade: This gets listed last because it’s a special, one-day event. From buttons to alfajores, everything’s rainbow, and you’ll see some “intriguing” costumes.

If you’re interested in shopping, there are always the malls her (called “Shoppings” by the Argentines), but they’re likely to be pricey. They’re much more elegant and elaborate places than those of the U.S., and if you decide just to go to check it out, it may feel like you’re walking in a hotel.

Best Museums

1. Evita Museo: If you love culture, this is for you.

2. MALBA: a Latin American arts museum with a huge and diverse collection, ranging from traditional to abstract and modern.

3. Museo Bellas Artes

4. Recoleta Centro Cultural

5. Trelew: Egidio Feruglio Museo: a small museum, good for an hour or so, but with impressively complete dinosaur skeletons.

6. San Antonio de Areco: Gaucho Museo: Ok

7. San Antonio de Areco: Cultural Museo: Don’t even bother, though it costs about one dollar and no guards will stop you from touching all the exhibits.

Transport

1. In the Hand: Buy yourself a Guía T and figure out how to use it. The bus stops are confusing, as the book will only tell you what street to look on, not what intersection, but it’s the best hardcopy map I’ve been able to find.

2. On the computer: To get a closer idea of where bus stops are, look at the routes and the bus suggetions online at http://mapa.buenosaires.gov.ar/

3. On the streets: The train (subte) runs quickly and until 10:30pm. After that, you’ve got to find a bus, or give in and take a taxi. Only take Radio Taxis, because sometimes you can end up with a bogus taxi who will rip you off, or worse.

Food

1. Lentil stew: it’s delicious; a thick stew, often with chunks of potato and beef.

2. Mandioca: this root actually comes from Paraguay, but is popular here, no doubt for it’s complex texture. “Chipas” are a dense, bagel-shaped food made from mandioca flour.

3. Alfajores: you’re obliged to try some, and they won’t be hard to find, whether you grab a packaged one from a kiosko or buy a fancier version at a bakery, and they vary a lot. The best I’ve had are AlfajOreos (this doesn’t really count: it’s more like a tall Oreo sandwich in a chocolate shell), maicena alfajores (soft cookies, thick dulce de leche filling, and rolled in shredded coconut), and a Vaquía brand alfajore well filled with a liquid Cappuccino filling.

4. Empanadas: as with alfajores, you haven’t been to Argentina if you haven’t tried one of these. They come in a huge variety, the most common being stuffed with ground beef or ham and cheese. I recommend corn or caprese-filled ones.

Bars:

I’m afraid I haven’t been to many, so this list will be short, sweet, and under-informed.

1. Acabar: board games, restaurant, and bar. What else could you want? Try the “Spare Time” drink: it’s neon blue and sweet. What else could you want?

2. El Alamo: my favorite straight-up bar, because the people are friendly and mix easily. You can get about 2 liters of beer for ridiculously cheap (I’d guess $5), if you’re into that sort of thing.

3. Jobs: another board game bar, far more elaborate than the other. There’s pool tables, darts, and, if you go on the right days (Saturday, Tuesday, Thursday), even archery. If you arrive before midnight you can skip the 30 peso cover charge and get a free pizza.

4.Shamrock: An Irish pub that varies a lot by the day; can be so crowded it’s a fight to get drinks, or can be a good time.

5.Le Bar: I can’t say much for the drinks, because I didn’t order one, but the ambience is nice. The seating is sunk into the floors, the lights are low, and you can go on the roof. The time I went there was a band, too.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

I Don’t Remember How . . . But the Terrorists Are Dead

This entry is immensely long, and it's also about one of the top two most interesting things I've experienced in Argentina.

In Full View

Twice a week Tribunal Oral en lo Criminal Nº1, a courthouse

in La Plata, Buenos Aires closes off the street in front of it, and holds a

trial on the rights abuses during the late 70s. This period in Argentina, from

1976-1983, is often called the “Dirty War”, except for by its victims, who

claim it was not a war, because a war needs two armies. Instead they use the

term “el Proceso” (“the Process”) to refer to 7 years of a government preying

on any citizen who spoke against it. While it is important to remember that the

citizens’ opposition was not pacifistic, they did not deserve what happened.

The

trial my class and I went to see was for information, not for a verdict. The defendant

on the stand Miguel Osvaldo Etchecolatz, the Director of Investigations for the

Police of Buenos Aires during the Proceso, had already been condemned to life

in jail in 2006. The trial was purely to find information, about a particular occurrence

during those years.

Anyone

with identification can enter a courtroom and watch a trial, and my school

group was joined by art students and some middle aged observers. One woman with

long white hair was a founding member of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a

group that still demands justice for the children the government secretly

kidnapped during the Proceso. The only rules the courthouse gave us were you

must be over fourteen, because the themes were so heavy, and you could not

bring in food or water, lest you throw them at someone. This implied the due

bitterness surrounding the trials. The courthouse staff gave us official

wristbands and let us enter.

Set the Stage

The

courtroom itself appeared to be an old theater. The seats the public sat in

looked just like those for a play-going audience, and a red curtain was pulled

to the side above the stage where sat the judge, defendant, and lawyers. Despite

its theatrical origins, it was a very plain building, devoid of any decorations.

A somber place dedicated to a practical job: finding the truth.

The

judge sat facing the audience, along with two assistants. (It surprised me to

see that one had dyed her hair magenta). On the right, rows of prosecuting

lawyers with laptops and coffee cups, faced inwards, towards center stage. On

the left, a cage jutted out into the audience, and here, protected by five

guards in bulletproof jackets reading “SPF”, sat the defense. One guard had a

riot shield, and they spent the time watching the audience and the case.

Throughout the trial more guards with radios and black berets walked the floor.

Etchecolatz

rose, a normal looking older man with white hair and a gray suit, and sat at a

desk, his back to the audience, facing the judge. This is what evil looks like, I told myself, knowing I was seeing a

man who had presided over murder and torture, and yet I felt no repulsion. This

was just a man.

Memory of Family

Etchecolatz had been called in from prison to give his account on the case of Casa 30. This house had been home to five Montoneros, anti-government rebels, and two of theirs baby girl. Most importantly, the house hosted a secret printing press the Montoneros used to distribute their political flyers. To cover it up, they raised and sold rabbits (as food, not pets). Because of this, the novel written about Casa 30 is called “Casa de Los Conejos”, or “House of Rabbits”.

Etchecolatz had been called in from prison to give his account on the case of Casa 30. This house had been home to five Montoneros, anti-government rebels, and two of theirs baby girl. Most importantly, the house hosted a secret printing press the Montoneros used to distribute their political flyers. To cover it up, they raised and sold rabbits (as food, not pets). Because of this, the novel written about Casa 30 is called “Casa de Los Conejos”, or “House of Rabbits”.

Etchecolatz and the police attacked

the house in 1976, killing everyone inside it, save, perhaps, for the three

month old baby, Clara Anahí Mariani. Neighbors reported seeing the police take

the baby from the house, and it was not an uncommon practice for police to

kidnap children and raise them as their own. Estimates say 400 of these

“disappeared” children are going about their lives today, completely unaware of

their real identities. Clara Anahí’s grandmother is still looking for her; if

she has survived this long, she turned 35 last August. But even if Clara Anahí

was taken alive from the house, she could have been hit by a car at age 15 and

died, or died of cancer at age 30; if alive she might not even still be in the

country. It soon became clear that Etchecolatz’s objective in the trial was to

say the daughter was dead, and thus that the search should stop, and that he was

not complicit in anything blameworthy.

Designing Justice

Trials in Latin America follow a different structure from the U.S.’s precedent-based system. The codified system in Latin America places more trust in written evidence and reviewing data, while the USA emphasizes oral evidence from witnesses. Watching this case, another difference became obvious: in Argentina, the judge, in addition to the lawyers, has a chance to examine the defense, and the defense can be brought in to be questioned again, if new evidence appears. For an hour or more, our judge questioned Etchecolatz

Trials in Latin America follow a different structure from the U.S.’s precedent-based system. The codified system in Latin America places more trust in written evidence and reviewing data, while the USA emphasizes oral evidence from witnesses. Watching this case, another difference became obvious: in Argentina, the judge, in addition to the lawyers, has a chance to examine the defense, and the defense can be brought in to be questioned again, if new evidence appears. For an hour or more, our judge questioned Etchecolatz

Summary: Ray of Truth, Fog of Lies

The events of the day at Casa 30 began to become clear as the trial proceeded. The facts that Etchecolatz and other accounts agreed upon were that Etchecolatz had arrived at Casa 30 along with other military officers, that several officers entered the house, and that the five Montoneros were killed. During the attack on Casa 30, Etchecolatz was on the roof of the adjacent house, along with a man with a bazooka.

The events of the day at Casa 30 began to become clear as the trial proceeded. The facts that Etchecolatz and other accounts agreed upon were that Etchecolatz had arrived at Casa 30 along with other military officers, that several officers entered the house, and that the five Montoneros were killed. During the attack on Casa 30, Etchecolatz was on the roof of the adjacent house, along with a man with a bazooka.

Etchecolatz handwaved over his

involvement, trying to suggest that his entire participation in the conflict

had been to merely exist on the roof, instead of having any job assigned to

him, or having been involved with organizing the event. The police director

also attempted to put a nationalistic, positive spin on the actions of the

police in the Proceso, presenting them as a civilian, humanitarian group, and

putting all blame for torture on the military. Part of Etchecolatz’s aim was

also to insist that the Proceso had not been unilateral aggression: “[Los

Montoneros] también tenía resistencia” (“The Montoneros also had resistance”) he said, and claimed

the guerrillas had killed 270 policemen.

There were a few notable flaws with

Etchecolatz’s account. First, he, the director of police, had followed someone

else’s orders to go to the house, and yet had not been assigned any role to do

while there. He hadn’t been on the roof to catch people fleeing, he insisted,

nor even really to observe. Secondly, all the Montoneros were to be killed and their

bodies burned, Etchecolatz reported, yet he claims neither saw bodies nor

flames nor heard shots. In regards to the detention centers, in Etchecolatz’s

world, the police were merely there to take care of the abducted people’s

health and nutrition, the rest was the military’s job. Finally, despite physical

evidence and numerous first hand accounts, Etchecolatz denied that torture was

a common occurrence.

In Defense of a Nation

When Perón ran for president in 1945, it was immediately

after World War II and photos of the concentration camps were just leaking out

to full public view. The U.S. ambassador, Braden, accused Perón of supporting

Hitler and harboring Nazis. To explain to the class why this was such a harsh,

campaign-damaging accusation, my history teacher clarified: it would be like

saying you supported the ESMA, a major detention center used in the Proceso.

Argentina is a place where those responsible for the Proceso draw a quicker gut

reaction, a more immediate repulsion, than Nazis. In my human rights classes

and history classes, no one could even question that the military committed

horrors.

Just thirty years after the

Proceso, and in a society where everyone knows the full extent of the abuses

committed, I heard Etchecolatz continue to assert that his actions were fully

justified. While I had been warned that most of the Proceso’s human rights

criminals were unrepentant, it still felt unreal. Etchecolatz referred to those

kidnapped by the government as “terroristas” (terrorists), and “prisioneros de la guerra” (prisoners

of war”).

“Tenían que perseguirlo [y] matarlos como ratas” (“We had to chase them [and]

kill them like rats”), he insisted; The Proceso was a campaign to protect country’s

institutions, and allow Argentina to live in peace.

Words for War

Among Etchecolatz’s description of the military government, stark nationalistic phrases continued to pop up. He told how the military government had tried to “recuperar la verdad” (“to recover the truth”), “recuperar lo que ha perdido” (“to recover what had been lost”), “[asegurar] respecta para sus instituciones” (“to ensure respect for its institutions”), “[asegurar que Argentina puede] vivir en paz” (“to makes sure that Argentina could live in peace”), “sofocar una situación de ofensa” (“to suffocate an offensive situation”), and “afrentar el enemigo” (“to confront the enemy”).

Among Etchecolatz’s description of the military government, stark nationalistic phrases continued to pop up. He told how the military government had tried to “recuperar la verdad” (“to recover the truth”), “recuperar lo que ha perdido” (“to recover what had been lost”), “[asegurar] respecta para sus instituciones” (“to ensure respect for its institutions”), “[asegurar que Argentina puede] vivir en paz” (“to makes sure that Argentina could live in peace”), “sofocar una situación de ofensa” (“to suffocate an offensive situation”), and “afrentar el enemigo” (“to confront the enemy”).

Brainwashed Language

During the Proceso itself, the government enacted a huge propaganda campaign in which they repeatedly used nationalistic images to present their work as glorious and righteous and encourage belief in their side. If the police and guerrillas clashed, the newspaper was bound to report that the police had eliminated a subversive, or, if luck went the other way, that a policeman had been murdered by terrorists.

During the Proceso itself, the government enacted a huge propaganda campaign in which they repeatedly used nationalistic images to present their work as glorious and righteous and encourage belief in their side. If the police and guerrillas clashed, the newspaper was bound to report that the police had eliminated a subversive, or, if luck went the other way, that a policeman had been murdered by terrorists.

Euphemisms made torture seem less

offensive: a “sumbarino” (submarine) is a tasty treat similar to hot chocolate,

made by dropping a bar of chocolate in warm milk. When the government attached

the name “submarino” to a form of torture, it became easier for soldiers to

distance themselves from what they were actually doing: waterboarding a victim

in water tainted with feces and urine. In a 1984-esque

attempt to cut down on subversive thought, the word “revolution” was banned,

even including in reference to science.

Play by Play

It feels the most honest representation is to report the

event as straightforwardly as possible, including giving the original Spanish,

as that is the most accurate and true wording. I will translate as closely as I

can.

What Did You Do?

It

began with the judge questioning:

“¿Cuándo

se producen muertes era porque hay sido resistencias?”

When killing occurred

was it because there had been resistance?

I didn’t

catch all of Etchecolatz‘s response. It was something like:

“Somos ciudadanos .. . . no es así

permitir abusos, no recibí ningún orden de torturas. . .”

We are citizens . .

.it is not so that abuses were allowed, I didn’t receive any order to torture.

. .

In a somewhat jumbled way,

Etchecolatz went on to detail the event. The government forces attacked Casa 30

because it had a printer for “panfletos terroristas” (“terrorist pamphlets”) in

the house. He believed that everyone in Casa 30 was killed, as the order had

been to leave no one alive (“nadie quedar con vida”). Officers entered that

house, the Montoneros inside resisted (at least he emphasized that he thought this was what happened), and,

presumably, said Etchecolatz, the officers killed them all. Still, he reminded

his listeners “no vi nada” (“I didn’t see anything”), and “no oí disparos” (“I didn’t hear shots”). Etchecolatz

said that “fueran carbonizados a todos en la casa” (“Everyone

in the house was burned to ashes”), but when the judge asked he admitted that

he had not seen fire or felt heat. Witnesses in other meetings on this case had

also not seen fire. According to my human rights teacher, it was a common

practice for the military/police to take away the bodies of their victims, so

as to leave no tangible evidence. If Etchecolatz could suggest the bodies were

burned, he would not have to explain what actually happened to them. But he

could not blatantly contradict the testimonies of other witnesses.

The

judge picked at the story:

“¿Por

qué estabas allá si hiciste nada? ¿Cómo fue estar en el techo sin ver nada?

¿Por qué estabas en el techo? Los disparos de afuera . . .estabas allá parar

matar a alguien que saliera de la casa?”

Why were you there if

you didn’t do anything? How was it that you were on the roof and saw nothing?

Why were you on the roof? The shots outside . . .where you there to kill anyone

who left the house?

Etchecolatz:

“Estaba allá por

parte de posición en la policía”

I was there as part of

my position in the police.

He

continued, saying that he was only support and that no one gave him an order.

Judge:

“¿Dices

que no hecho ningún tipo de exceso? ¿Nunca influido por exceso del gobierno de

este época?”

You said that you

never committed any type of excess? You were never influenced by the excesses

of the government of this time?

Etchecolatz:

“Lo que

cumplí estaba acuerdo del ley”

What I did was in

agreement with the law.

Judge:

“Si recibió un orden a matar, debió

negar”

If one received an

order to kill, one should refuse it.

Etchecolatz:

“¡Ningún

orden matar!”

There wasn’t any order

to kill!

Etchecolatz continued, saying that he had only received

orders to go to the roof.

Vanished Children

Judge:

“¿Hijos

de personas desaparecidos eran recobrados?”

Were the children of

the disappeared recovered?

Etchecolatz:

“No sé.”

I don’t know.

In

regards to the child Clara Anahí, Etchecolatz merely mentioned that the

people in the house

“enseñaba a niña revistas subversivos” (“taught the girl subversive magazines”);

this is no doubt a major reason the military would have taken her. El Argentino, a newspaper present at the

trial that day, quoted Etchecolatz as saying “No puedo asegurar que la

criatura estaba adentro, pero si estaba adentro, la criatura no pudo salir con

vida” (“I can’t be sure that the child was inside, but if she was inside, the

child could not have left with her life”). Despite this claim, it is known,

thanks to a testimony in El Argentino,

that the police had at one point attempted to sell Clara Anahí to her

grandmother, something that strongly suggests the child was not killed at the

house. Relatively recently, it was thought that the daughter of the owner of Clarín, an important newspaper, was in

fact Clara Anahí. The daughters looked similar, were of the right age, and it

was known that the newspaper owner’s daughter was adopted under strange

circumstances. For much time the newspaper owner’s lawyers stalled and resisted

requests for a DNA test, then suddenly agreed to it, presumably because they

discovered through other evidence that the daughter was not a match.

A Skeptical Audience

In response another line of questioning, Etchecolatz told the judge that whatever happened to pregnant women was the decision of the clandestine detention centers that held them, and was not his fault. The police, he said, were only responsible for the health and food of the prisoners, nothing else. The police’s orders, he reiterated, were to “mantener higiene, cuidar salud física, no interrogar” (“to maintain hygiene, to take care of physical health, not to interrogate”). The military was the one who had the responsibility for the prisoners and the detention centers.

In response another line of questioning, Etchecolatz told the judge that whatever happened to pregnant women was the decision of the clandestine detention centers that held them, and was not his fault. The police, he said, were only responsible for the health and food of the prisoners, nothing else. The police’s orders, he reiterated, were to “mantener higiene, cuidar salud física, no interrogar” (“to maintain hygiene, to take care of physical health, not to interrogate”). The military was the one who had the responsibility for the prisoners and the detention centers.

However, Etchecolatz said he did

remember one instance of a pregnant prisoner. When this girl gave birth, he

said, the staff at the detention center bought her presents and a card. Groans

of disbelief rose from the audience when they heard this. He couldn’t remember

the girl’s name or last name. But she was from La Plata, the neighborhood the

trial was in, he said, and the police, because it was a humanitarian issue,

took charge of letting her family know.

By this point, the audience had seen

thousands such trials, and knew to expect these sort of responses from the

accused. In 1986 it was prohibited to try anyone for human rights abuses

committed during the Proceso and since then many criminals were pardoned. About

a decade ago, then-president Néstor Kirchner re-opened the trials. The lying

and lack of repentance was nothing new to the audience of this trial, and the

bitterness was clear. When Etchecolatz announced that “caminaba en lo más sucio de la sociedad y

no me contaminaba” (I walked in the filthiest part of society, and it

didn’t contaminate me”) members of the audience laughed aloud in scorn.

Remember with Care

When the judge returned to asking Etchecolatz about the events on the day at Casa 30, Etchecolatz tried to say he didn’t remember much of anything. Occasionally, in the trial Etchecolatz would get flustered responding to questions, would answer in a stream of “Sísísísísí” or “Nononono.” After prodding, he admitted he did remember how he arrived (in a car), but not who drove it, and admitted that he did now remember that others were in the car with him. He did not remember, however, who ordered the attack on the “casa de los terroristas” (“the terrorists’ house”). As Etchecolatz was the director of the police, it is a fair bet that he himself ordered the attack.

When the judge returned to asking Etchecolatz about the events on the day at Casa 30, Etchecolatz tried to say he didn’t remember much of anything. Occasionally, in the trial Etchecolatz would get flustered responding to questions, would answer in a stream of “Sísísísísí” or “Nononono.” After prodding, he admitted he did remember how he arrived (in a car), but not who drove it, and admitted that he did now remember that others were in the car with him. He did not remember, however, who ordered the attack on the “casa de los terroristas” (“the terrorists’ house”). As Etchecolatz was the director of the police, it is a fair bet that he himself ordered the attack.

Here the lawyers took over.

One asked:

“¿Si no

estaba parte de investigaciones, si solo cuidaba salud física, porque estaba a

la Casa 30?”

If you weren’t there

as part of the investigations, if you only took care of physical health, why

were you at Casa 30?

I don’t believe Etchecolatz answered this one.

House of Holes

After the trial, we went to see Casa 30, a small gray cement building. A

whole window and most of the wall was blasted out, presumably by the bazooka,

and deep holes marked around the door and wall. Glancing through a bullet hole

on one wall we could see inside the house, a wall similarly pockmarked by bullets.

The roof Etchecolatz must have stood on could not have been more than 8 feet

from the door of Casa 30.

Epilogue: The Curtain Doesn’t Fall

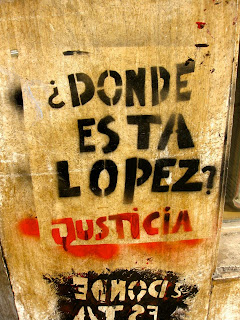

The face and name Jorge Julio López is something I've seen graffitied all across Buenos Aires, on walls, on tiles in La Plaza de Mayo, and especially in La Plata. Eventually, I learned why.

in La Plata

at Plaza de Mayo

This man had been kidnapped and personally tortured by

Etchecolatz from 1976-1979. During the first trial of Etchecolatz, López was a

major witness, and his testimony against Etchecolatz was invaluable: In

addition to recounting to his own horrific experience, López had seen

Etchecolatz execute five people.

Though the Proceso trials offer a form of resolution

and validation, testifying is nonetheless extremely painful for the victims. In

a documentary on this trial, called “Un Claro Día de Justicia” (“A Clear Day of

Justice”), I saw López struggling to get the words out. He remembered a woman

named Patricia who was imprisoned with him; he was the only one of them with a

chance of leaving the detention center alive, she told him, and she begged

López to find her parents or her brothers and tell them to “dame un beso a mis

hijas” (“give a kiss to my daughters for me”). Recounting, reliving, this

moment, López’s voice almost failed him, it was with painful effort that he

managed to speak. The older man’s hands trembled, like a hummingbird flapping,

so much that he couldn’t pick up a glass of water; someone had to hold it out

for him to sip.

López during the trial. (Photo credit to Haydeé Dessal y Elena Luz González Bazán at http://www.villacrespomibarrio.com.ar/2011/septiembre/ciudad/derechos%20humanos/lopez%20en%20fotos.htm)

It was 23 years after the end of the Proceso, supposedly in a better government and better world, and yet, with López’s abduction, the disappearances were re-opened. Since then, there have been accusations the police’s fruitlessness in the case is deliberate. The satire magazine, Revista Barcelona, publishes a weekly piece ridiculing the police’s attempts to find López. Clara Anahí and Jorge Julio López have still not been found, but until they, or their final resting places are, the trials will still go on, and the protests will continue in the Plaza de Mayo.

Calendar titled "How many days without López?"; Displayed in ESMA, previous site of a navy clandestine detention center.

Links:

López’s testimony (in Spanish): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ayyh_169cF8

López’s disappearance (in English): http://www.argentinaindependent.com/currentaffairs/analysis/leave-no-stone-unturned-the-disappearance-of-jorge-julio-lopez-/

Clara Anahí (in Spanish): http://www.elargentino.com/nota-152530-Los-chicos-recuerdan-a-Clara-Anahi-a-35-anos.html

The trial, El Argentino article (In Spanish): http://www.elargentino.com/nota-165038-Etchecolatz-a-Chicha-A-Clara-Anahi-se-la-quito-la-subversion.html

Monday, November 14, 2011

Pretty Places: Iguazú

This time we took a few days and went north, up to Iguazú Falls, which is currently a candidate for one of the 7 Natural Wonders of the World (there’s an on-going vote). I just got back this afternoon.

When atomic bombs had just roared into the world’s consciousness, people had no idea what they would do. They were terrified of all sorts of things: that atomic bombs would reverse the earth’s magnetic poles, or, my favorite, that they would blow a hole in the earth so big all the ocean’s would drain through. Iguazu Falls looks like this. All the water is just dropping away, cascading forcefully into a void of white mist. A few sparrows flit in and out of the fog of spray, the only small black marks on an endless white.

Walkways have been set up so you can get close to the immense series of falls, and stand atop the point where river turns to falling rapids. Other walkways give you full views of the fall. Looking out at the palm trees, thick growths of vines and tall forests that cover the islands, my friend Shaina said something I couldn’t agree with more, it was like being in the land of the dinosaurs. Still for me, while the views were fantastic, walking across an even metal platform to get there made me feel even more distanced from the experience, even more like a tourist.

I have a thing about texture. So much of daily life is visual, and everything seems to be smooth: chairs, tables, the computer mouth, the glasses, book covers. Modern society has a plethora of colors but little variety for the other senses. The point being, I wanted to feel that I was somewhere new, not just see it.

We managed to shake things up a bit. We took a boat ride across one of the rivers. It was a peaceful affair, nice but not super exciting. That was our next boat trip. A speed boat brought us right under the falling water, so it pounded on us, making it almost impossible to open our eyes, hard for some people to even breath. I loved it. The water is relentless, and soaked us through, a welcome change from the humidity.

Back at the town we cooled off with some oddly flavored ice cream, including Kiwi and Yerba Mate.

Our second day was charged with thunderstorms, which cut short our trek through the jungle itself. This dirt path went to a waterfall where you could swim around, but we never got that far. Not swayed by my insistence that we probably wouldn’t be hit by lightning yet, a friend decided it was time to turn around. The mud was red like we’d found Mars, and the jungle grew thick around us. It seems tame from a wide path, but it must have been terrifying to be the first to hack through plants so thick they cut out almost all light.

As we began to head back, a coapi (kind of like a long-nosed raccoon) ran across our path. I had lost my camera case in Santa Tierra, so was storing it in a sock and a plastic grocery bag. I began to pull it from my pocket, thinking a coapi on our path would, honestly, make a nice addition for Facebook. The plastic rustled. The coapi turned. We’d been warned these creatures get violent around food and not to feed them. (Presumably coapi are like geese, in that if you offer geese a piece of bread, the birds assume this is it only because you have an infinite storage of bread to give them. If you do not then feed the geese to the point of bloating, they assume you are holding out on them and express this in a fit of bitey rage.). And coapi have sharp teeth. And claws. The animal walked over to my friend, and we both held very still. Possibly he (she?) smelled leftovers from lunch in her bag. I moved away and my plastic bag, now in my hand, inadvertently rustled again, which drew the coapi to me. I held the bag away from my body and let him examine it, thinking he would see it wasn’t food, and let us be. The coapi came to his hind legs and pawed the bag, and I let him take it. He tore it open and found a very non-tasty sock. The problem started when he grabbed the sock in his mouth and began to hop away, back into the jungle, taking my photos and pricey camera with him. Fortunately, when I stamped the ground he dropped it and wandered off a bit.

a different coapi, earlier on

Our third and last day, we found that rainforests do, in fact, rain. It downpoured, which kept us inside a lot, playing endless matches of foosball. (Not really complaining there). There’s not much to do inside in Iguazú, unless you go to the shopping mall or casino. We braved the rain and went to Guira Oga, an animal rehabilitation center. Here, jungle animals who have been kept as pets or smuggled around are rehabilitated. (One set of monkeys had previously been pets. There mother was shot and they were drugged with water laced with wine then taken to be sold). They may be released again into the wild, but more likely they’ll just be taken care of in a more natural way and their children will be put back in the wild. Injured animals are also taken in, including one bird who’s jaw had been shot off by a hunter.

It was interesting to see the animals, all in large caged off areas. They were in pens in a jungle, but it wasn’t the same as seeing wild animals. The difference was, they weren’t afraid of us, and, more importantly, we weren’t afraid of them. I saw several coapis in the rehab center being treated for diabetes they had developed after eating tourist’s chocolates and processed food. My first instinct, glimpsed their fuzzie heads, was to think how adorable they were, before I recognized them as threatening little camera-thieves.

My favorites were seeing a toucan (not as big as I would have thought) and a type of monkey that looks like a bush. The bush-monkeys were huddle in the rain, just two furry spheres squatting on the handrail. Apparently the female monkeys are the territorial ones and will claim an area and a mate. We were warned not to get too close or the she would get angry; regardless whether your human or even another species of monkey, these females will see you as a threat. The bush-monkey had been give a trainer to help rehabilitate her (I’m not sure what the problem was) but the trainer was a woman, so she’d have none of it.

Traveler’s Tips

How to Arrive

How to Arrive

Our bus was Crucero del Norte, and the best we’ve been on. The food varies from tasty chicken to airplane food (in a flash of Americanism, I dreamed of salad, and received fast food French fries and a Milanese covered in cheap cheese. Still, they give you alright food). The bathrooms are both clean and have toilet paper and soap (most bars don’t even give you that much). The buses to arrive and to leave both arrived pretty much on time, even according to American standards.

Where to Stay

We stayed at Hostel Park Iguazu. It was decent, with a full-sized pool, a foosball table, 2 computers, and hammocks. At least one of the desk attendants knew English, and the rooms, though small, were fine, save from 2 cockroaches.

(After our failed attempts to catch cockroach, a friend went to the desk, and not even trying Spanish, announced, “Bug. Big one.” The attendant gave her two plastic cups and a can of Raid. She came back: “It got away into the ceiling” she told him. “Why don’t you keep the can?”, he said.”)

What to Do

The tours we did are common and you’ll see a “Jungle” stand at the park offering them. The boat Eco tour down the river isn’t worth the price for just it (we got it in a deal with the other trip, costing only 35 pesos more). It’s not very exciting, and you can only hear the guide if you sit really close to him (and speak Spanish). You might see animals, but you might not. We didn’t.

The under the waterfall tour can be done for about 135 pesos or so, which we did, or combined with a on the rapids ride and a jeep ride through a jungle, for 200-something pesos.

We were planning on paying 200 pesos to walk the Devil’s Throat (Garganuta del Diablo) path at night, but it got rained out. They’re very good at giving you your money back if you cancel.

I recommend Guira Oga, the animal refuge we went to. It cost 40 pesos, and is offered even in the rain. Our guide only spoke in Spanish, and wasn’t great about waiting until everyone was there to hear her, but you see cool animals, and it’s certainly worth the price.

You can get tickets to the falls and to Guira Oga at the bus terminal in the town for 10 pesos each way. Tell the bus driver when you get on if you want him to stop at Guira Oga. You may be able to only pay 4 pesos just to go to Guira Oga, but the terminal will charge you 10 if you buy from them. I believe you can just hand the bus driver cash directly.

What to avoid

Even though the park's water fountains advertise 24hour purification, don't risk drinking the water. A friend of mine made this mistake, and it more or less took her out of commission for a day and a half. (I can't promise that this was the culprit, but we can't think of any other reason). She threw up that night, and didn't feel well enough to hike much the next day.

Brazil

If you're like me, your guidebook told you Americans can waltz into Brazil without paying a fee, if they only plan to stop over for the day. This, it seems, is a cruel cruel lie. According to our hostel and everyone we asked, Americans need to go to the Brazilian representative and apply for a pass into the country, which may take about a day to get and may costs about $100 or $140 (my memory fails me). This is a reciprocation fee, which Brazil charges because the US does the same to it. The majority of the falls are on the Argentinean side, and while going into Brazil means you see Iguazú from all angles, it doesn't offer you much that's new or different. At the very least, that's what I've come to feel after talking to traveler's coming over from the Brazil side: Argentina's section is just larger and more impressive. If you feel daring and don't have a problem with illegality, you can try taking a taxi into Paraguay (which is free), and from there travel into Brazil.

Paraguay

I didn't go there myself, but I've been told that area of Paraguay close to Iguazú is appreciated for very cheap goods, but not for sightseeing. Argentineans and tourists will cross over to stock up on clothes and souvenirs.

What to avoid

Even though the park's water fountains advertise 24hour purification, don't risk drinking the water. A friend of mine made this mistake, and it more or less took her out of commission for a day and a half. (I can't promise that this was the culprit, but we can't think of any other reason). She threw up that night, and didn't feel well enough to hike much the next day.

Brazil

If you're like me, your guidebook told you Americans can waltz into Brazil without paying a fee, if they only plan to stop over for the day. This, it seems, is a cruel cruel lie. According to our hostel and everyone we asked, Americans need to go to the Brazilian representative and apply for a pass into the country, which may take about a day to get and may costs about $100 or $140 (my memory fails me). This is a reciprocation fee, which Brazil charges because the US does the same to it. The majority of the falls are on the Argentinean side, and while going into Brazil means you see Iguazú from all angles, it doesn't offer you much that's new or different. At the very least, that's what I've come to feel after talking to traveler's coming over from the Brazil side: Argentina's section is just larger and more impressive. If you feel daring and don't have a problem with illegality, you can try taking a taxi into Paraguay (which is free), and from there travel into Brazil.

Paraguay

I didn't go there myself, but I've been told that area of Paraguay close to Iguazú is appreciated for very cheap goods, but not for sightseeing. Argentineans and tourists will cross over to stock up on clothes and souvenirs.

Pretty Places: Tigre

About two months ago I took a weekend trip to an area called Tigre, with a group from my program. It’s a beautiful Argentine get-away on a muddy river (darkened by sediment, not pollution). The area seems mostly inhabited by vacationers and those who run businesses for vacationers, and is known for a fruit fair.

Right about now, in full summer, the area would be at it’s best, I think, because it will be warm enough to swim and the flowers will be more in bloom. As it was, it was a great place; we pedal boated and kayaked, walked around the woods, and played Scrabble in Spanish.

Our program organized the hotel, and as we looked around at the 2 person luxury cabins in the woods we’d been assigned to, we realized we’d been placed into a honey moon suite. It even came with a sexy music CD and beds that slide together.

While made a few more small steps of food tasting in the name of one large step for foodiekind. Some of the more intriguing elements were cow kidneys, a new type of blood sausage, cow gullet, and cow intestine. The blood sausage was lumpier and less intense than what I’d been given at my first homestay; I rate this an improvement. I couldn’t finish the kidneys, thanks to their overpowering flavor. The intestine itself had no offensive taste, and was overcooked to be very chewy. Victory went to the gullet, which I really just remember as being kind of soft.

I also came to realize that in regards to alfajores, the maicena kind is where it’s at. These are more likely to have a thicker dulce de leche filling, instead of a token coating, and the dense cookies of these don’t taste artificial, unlike the average kiosko alfajore.

If I remember correctly, the dark one is blood sausage, and the kidney is speared on the fork.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Saint Land

“Tierra Santa”; Buenos Aire’s Jerusalem theme park. The park was not the tacky, touristy travesty that we had all hoped for, but still made a fun outing. The whole place was full of plastic Middle Eastern buildings and statues recreating scenes like Jesus expelling the money lenders. (There were even plastic palm trees next to the real palm trees, as if the parks’ designer didn’t realize that these things actually grow in Argentina). The tranquil music in the park actually set the stage well, and I was thrilled to see Roman guards wandering around, and people in Arabic style clothing sweeping. (Not to mention that it was awesome to finally be able to buy hummus and eggplant for lunch). I also desperately wanted to go on the merry-go-round (which featured donkeys, camels, and an angel on top), but, tragically for my merry-go-round fixation, it was closed. And only for children. We did go to see the several shows the park offers, including the Creation of the Universe, recreated through neon lights and moving robots of the first life.

The crowning moment was the Resurrection show, when a gigantic, 20-foot tall Jesus rose from the top of a hill to the sound of “Hallelujahs”.

GayZombieLaws

Yum yum diversity.

Gay Pride

Yesterday, I went to a gay pride parade, which turned out not to be a parade, but a plaza full of stands selling rainbow colored goods. Given Argentina’s love affair with fairs, it was actually rather fitting. A few of the more interesting merchandise included rainbow colored alfajores and chocolate popsicles shaped like penises. The event also attracted a few elaborate costumes, such as a woman dressed solely in one yellow thong and gold sparkle body paint, and a variety of drag queens. (One man, dressed in a dominatrix costume, was immediately encircled by cameras. He kept having to turn and turn to face each new camera that surrounded him. I felt like I was watching a captured animal, that instead of frightened, was sultry).

Gay pride is different in Argentina, where although prejudice still exists, gay marriage is legal throughout the country. There was one stand protesting against the church and calling for a greater separation between church and state, which leads me to believe the marriage is still a big issue, just civil unions are legal. Still, the focus of this event was transgender people. They are not allowed to change their national IDs to state their preferred gender, which in many ways can make them easy targets (as any police can see, for example, that Laura looks feminine, but her ID still says “male”), and it can cause hassles. One of my friends’ professors at the UBA is transgender, and the bathrooms are swipe-to-enter. Though the professor looks male, he can only access the women’s bathroom, and the police have been called on him twice for being a man in a woman’s bathroom. (Why you would call the police about this is another question . .. .). Tuesday, the government votes to change this transgender-ID policy.

Abortion

Another vote that recently failed by just 2 signatures was to legalize abortion. Right now, you can only have an abortion if you are both mentally disabled and raped. (It used to be either disabled OR raped, but in a rewriting of the constitution, someone changed it. Or thus says my history teacher).

Economy

In other legal news, a few days back Argentine prohibited it’s people from buying U.S. dollars. The peso’s value is based on the dollar, so many people, not trusting the Argentine economy, have been just buying dollars hoping they’re more secure and because they’re rising in value (much like we’d buy gold). It’s also important, because here you can only make major purchases in dollars (for instance, buying a house), and other countries won’t accept pesos, so if you travel to Uruguay, for example, you’ll need to change currency first.

I’m not quite sure why Cristina blocked purchases. According to an economist I met on the street, it costs a government a lot to keep buying foreign currency to supply to their citizens (likely that, just like banks mark up the price when they sell you currency, other countries do this too). Also, forcing people to use pesos means that money stays in Argentina and gets invested here, instead of sent out of the country. Still, the lack of being able to buy costly things is going to be a major problem.

School

Friday there were only about 7 students who came to the school I help out with. It turns out, the teachers in the village are on strike so the kids neither have classes or homework. Apparently this is common; the teachers are always negotiating better deals, and if they don’t like the compromises, they strike. I know in the U.S. some Sates legally prohibit teachers and other public employees (like postal workers and police) from striking.

Zombies

The lack of marching at the gay pride parade also reminds me of the lack of walking at the zombie walk last weekend. It seems Argentines are a sedentary people. The zombie “walk” was still an interesting event: a plaza full of costumes, and Argentine geek culture. Those who didn’t dress up often wore metal band T-shirts (Iron Maiden seems to be popular here), and I caught a glimpse to El Eternauta. I didn’t dress up, but I did dance Thriller.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)